This transcript has been edited for clarity.

The other day, my 7-year-old asked me why all the good-tasting foods are junky and all the healthy foods are yucky. And that's the rub, isn't it? We have evolved to enjoy high-calorie–, high-salt–, high-sugar–containing foods because we evolved in a time of scarcity. And, for the developed world at least, that time is past.

In this time of plenty, where delicious-tasting, if unhealthy, foods are ubiquitous, is it any wonder that so much time has been spent trying to find substances that taste good without all the baggage that comes with, say, sugar?

Enter sugar substitutes, a $10 billion–dollar industry. The field is varied and includes small molecules and polypeptides, artificial sweeteners, and so-called "natural" sugar alternatives, all brought together by the simple fact that they bind to the sweetness receptors on taste buds.

And it is one of those sweeteners — erythritol — that we are going to talk about today in an ongoing series that we should really call "Is This Thing That You Eat Everyday Secretly Killing You?"

Erythritol is a sugar alcohol found in nature, meaning that manufacturers do not need to label it as an artificial sweetener. And as far as nonnutritive sweeteners go, erythritol has a lot to recommend it.

It's about the same sweetness, gram for gram, as sucrose, so you can basically swap it into a recipe without changing anything. We can't get energy out of it; while rapidly absorbed through the small intestine, the vast majority or erythritol is excreted unchanged in the urine. Oral bacteria can't metabolize it either, meaning it won't contribute to tooth decay, and multiple studies have shown that it doesn't increase blood sugar or insulin levels.

So why bother talking about this natural, tasty, apparently safe food additive? Well, because according to an article in Nature Medicine, it may contribute to heart attacks. This is a nice paper that synthesizes multiple lines of evidence to make an argument that erythritol may be dangerous. I'm not sure it gets there, to be honest, but let's review the evidence first.

The researchers started with a metabolomic analysis of just over 1000 people being assessed for heart disease. Modern metabolomic studies look at the levels of hundreds, sometimes thousands, of metabolites circulating in the blood to see which might be associated with a given disease. In this case, focusing on sugar and sugar-substitute metabolites, erythritol topped the pack.

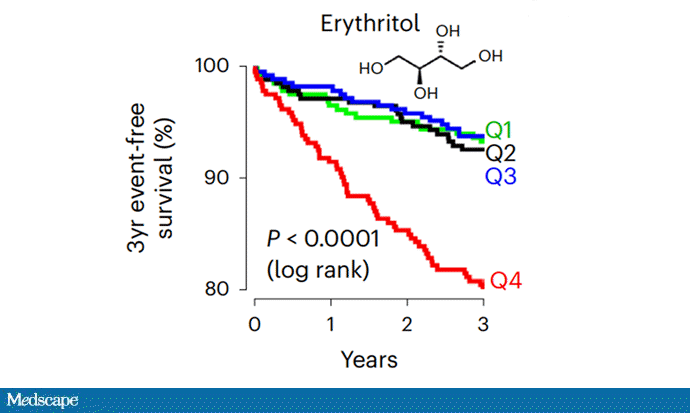

Those who would go on to have a major adverse cardiovascular event had significantly higher erythritol levels at baseline than those who would not.

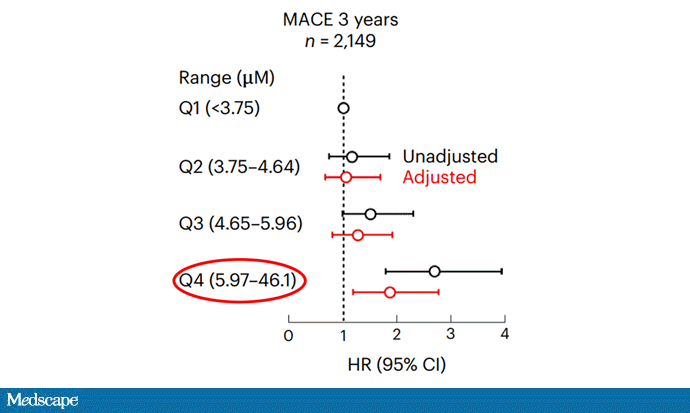

There are two problems with this, though. First, because metabolomic studies check so many metabolites, you are essentially guaranteed to get some strong hits just by chance alone. They need to be replicated in validation sets. The authors did this, showing in an independent American dataset that those in the highest quartile of erythritol levels were much more likely to have a major heart event in the future.

Of course, this brings us to the second problem. Just because erythritol levels are higher in people who go on to have heart attacks doesn't mean that erythritol causes the heart attacks. People who consume sugar substitutes may be different in important ways compared with those who don't; think factors like diabetes, BMI, even socioeconomic status. The authors adjusted for many of these, but as we've said many times before, perfect adjustment is impossible.

I should also mention that we make small amounts of erythritol ourselves regardless of whether we eat it.

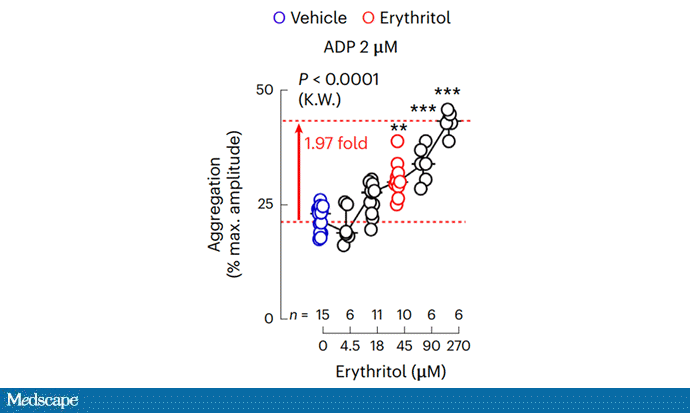

The study gets more interesting, though. The authors clearly wanted to see, if erythritol had a causal link to cardiovascular disease, what would the mechanism be? They hypothesized that erythritol in the blood might stimulate platelets to clump together more easily — to clot, in other words. Sure enough, that's just what they found. In a test tube, as the concentration of erythritol was increased toward 45 micromolar, platelets began to get quite a bit stickier.

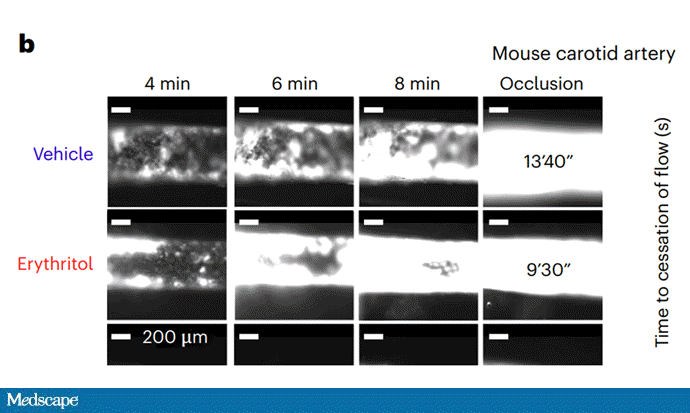

This had real clinical consequences, in mice at least. In an experimental model of time-to–carotid artery occlusion, mice exposed to erythritol had faster clotting.

Okay. If there's one thing I've learned from reading studies of artificial sweeteners, it's to check the concentrations. It's one thing to say that a given sweetener causes cancer in rats when fed 100 times the typical daily dose. It's quite another to say that this occurs at physiologic levels.

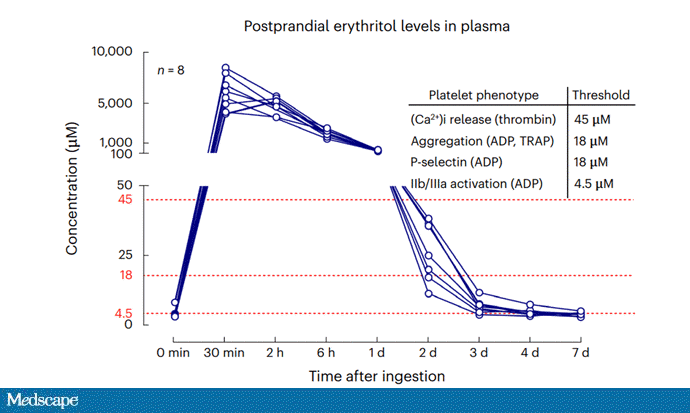

So, 45 micromolar — that's the concentration where all this platelet action is seen. Can we put that in context? Well, in the American validation cohort, the highest quartile of erythritol levels comprised people with levels ranging from 6 to 46 micromolar. So, right off the bat, it's clear that 45 micromolar is on the high side.

Of course, maybe you don't need your erythritol levels to be 45 all the time; maybe just spiking up there for a while can increase clotting. To assess this, the researchers measured erythritol blood levels in eight healthy controls after consuming 30 g of an erythritol slurry.

You can see that blood levels can get incredibly high and stay above 45 from about 30 minutes to 2 days after that ingestion.

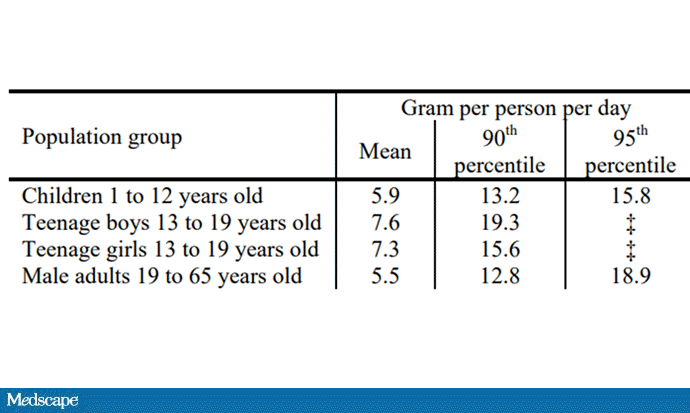

If we want to put this together, we can probably say that you might not want to eat or drink 30 g of erythritol every day. The authors argue that 30 g is exactly what we're taking in per day, citing an FDA filing, but I dug into that and 30 g is actually the 90th percentile of intake in the United States, with the mean reported at 13 g.

And even that seems too high. This food diary study from Europe estimates daily intake at about 5 or 6 g. And that's among people who reported using all sugar-free products in their daily consumption.

So, no, I'm not terribly worried right now about my monkfruit sweetener, or my sugar-free gum, or my toothpaste. While the harms from sugar substitutes are still mostly theoretical, the harms of sugar are all too real. Erythritol may well be the lesser of two evils here. It would be great to have all the sweetness of sugar and none of the harms. Of course, I'm reminded of a truism when it comes to the science of diet: It's rare that you can have your sugar-free cake and eat it too.

F. Perry Wilson, MD, MSCE, is an associate professor of medicine and director of Yale's Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator. His science communication work can be found in the Huffington Post, on NPR, and here on Medscape. He tweets @fperrywilson, and his new book, How Medicine Works and When It Doesn't, is available now.

Follow Medscape on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and YouTube

Credits:

Image 1: Nature Medicine

Image 2: Nature Medicine

Image 3: Nature Medicine

Image 4: Nature Medicine

Image 5: Nature Medicine

Image 6: Nature Medicine

Image 7: European Food Safety Authority

Medscape © 2023 WebMD, LLC

Any views expressed above are the author's own and do not necessarily reflect the views of WebMD or Medscape.

Cite this: F. Perry Wilson. Sweet on Erythritol? Sugar Substitute Linked to Heart Disease - Medscape - Feb 28, 2023.

Comments