This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Welcome to Impact Factor, your weekly dose of commentary on a new medical study. I'm Dr F. Perry Wilson of the Yale School of Medicine.

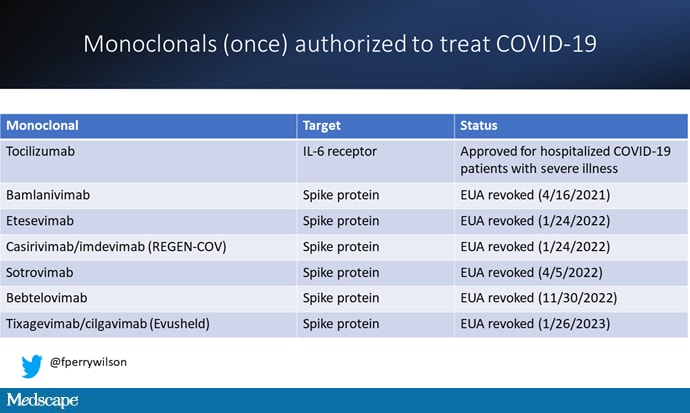

With SARS-CoV-2 sidestepping monoclonal antibodies faster than a Texas square dance, the need for new therapeutic options to treat — not prevent — COVID-19 is becoming more and more dire.

At this point, with the monoclonals found to be essentially useless, we are left with remdesivir with its modest efficacy and Paxlovid, which, for some reason, people don't seem to be taking.

Part of the reason the monoclonals have failed lately is because of their specificity; they are homogeneous antibodies targeted toward a very specific epitope that may change from variant to variant. We need a broader therapeutic, one that has activity across all variants — maybe even one that has activity against all viruses? We've got one. Interferon.

The first mention of interferon as a potential COVID therapy was at the very start of the pandemic, so I'm sort of surprised that the first large, randomized trial is only being reported now in The New England Journal of Medicine.

Before we dig into the results, let's talk mechanism. This is a trial of interferon-lambda, also known as interleukin-29.

The lambda interferons were only discovered in 2003. They differ from the more familiar interferons only in their cellular receptors; the downstream effects seem quite similar. As opposed to the cellular receptors for interferon alfa, which are widely expressed, the receptors for lambda are restricted to epithelial tissues. This makes it a good choice as a COVID treatment, since the virus also preferentially targets those epithelial cells.

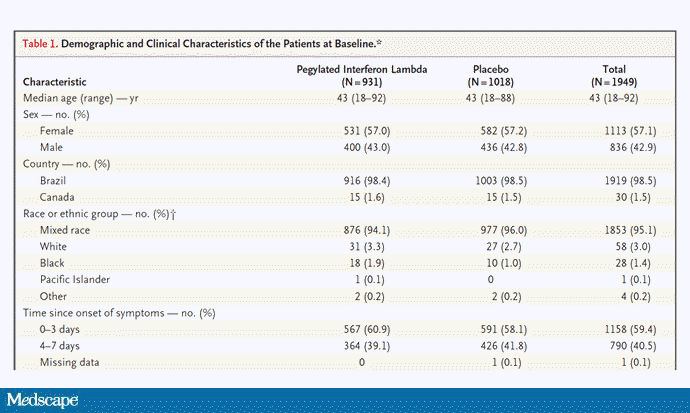

In this study, 1951 participants from Brazil and Canada, but mostly Brazil, with new COVID infections who were not yet hospitalized were randomized to receive 180 µg of interferon lambda or placebo.

This was a relatively current COVID trial, as you can see from the participant characteristics. The majority had been vaccinated, and nearly half of the infections were during the Omicron phase of the pandemic.

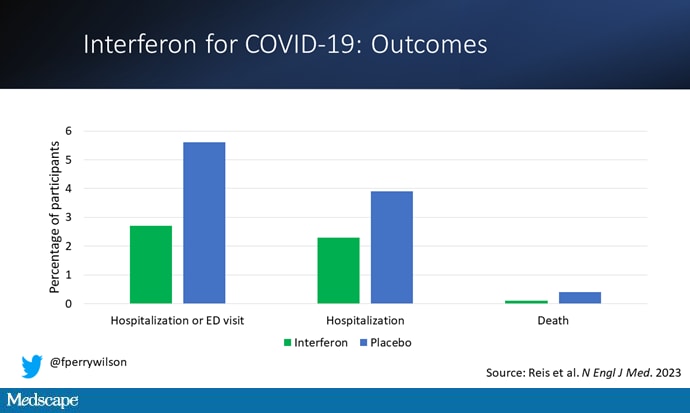

If you just want to cut to the chase, interferon worked.

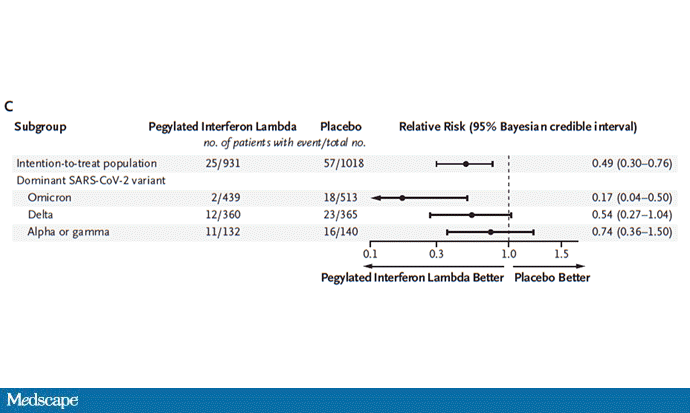

The primary outcome — hospitalization or a prolonged emergency room visit for COVID — was 50% lower in the interferon group.

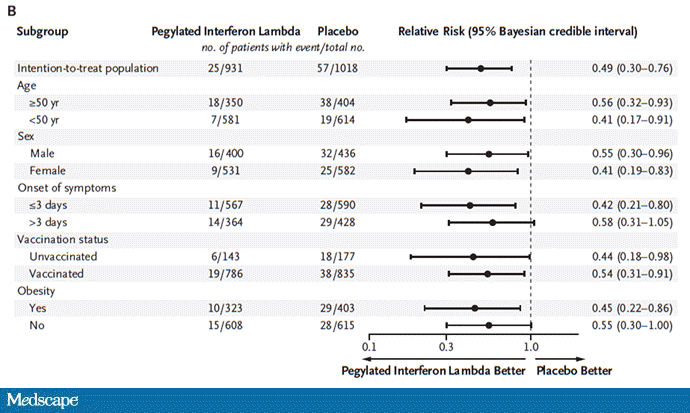

Key secondary outcomes, including death from COVID, were lower in the interferon group as well. These effects persisted across most of the subgroups I was looking out for.

Interferon seemed to help those who were already vaccinated and those who were unvaccinated. There's a hint that it works better within the first few days of symptoms, which isn't surprising; we've seen this for many of the therapeutics, including Paxlovid. Time is of the essence. Encouragingly, the effect was a bit more pronounced among those infected with Omicron.

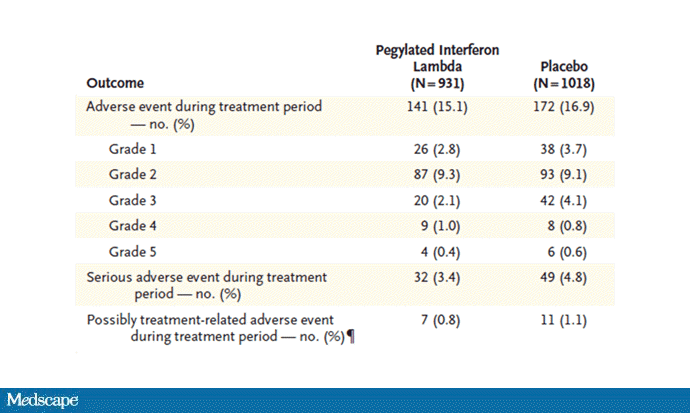

Of course, if you have any experience with interferon, you know that the side effects can be pretty rough. In the bad old days when we treated hepatitis C infection with interferon, patients would get their injections on Friday in anticipation of being essentially out of commission with flu-like symptoms through the weekend. But we don't see much evidence of adverse events in this trial, maybe due to the greater specificity of interferon lambda.

Putting it all together, the state of play for interferons in COVID may be changing. To date, the FDA has not recommended the use of interferon alfa or -beta for COVID-19, citing some data that they are ineffective or even harmful in hospitalized patients with COVID. Interferon lambda is not FDA approved and thus not even available in the United States. But the reason it has not been approved is that there has not been a large, well-conducted interferon lambda trial. Now there is. Will this study be enough to prompt an emergency use authorization? The elephant in the room, of course, is Paxlovid, which at this point has a longer safety track record and, importantly, is oral. I'd love to see a head-to-head trial. Short of that, I tend to be in favor of having more options on the table.

For Medscape, I'm Perry Wilson.

F. Perry Wilson, MD, MSCE, is an associate professor of medicine and director of Yale's Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator. His science communication work can be found in the Huffington Post, on NPR, and here on Medscape. He tweets @fperrywilson and his new book, How Medicine Works and When It Doesn't, is available now.

Follow Medscape on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and YouTube

Credits:

Image 1: F. Perry Wilson, MD, MSCE

Image 2: The New England Journal of Medicine

Image 3: F. Perry Wilson, MD, MSCE

Image 4: The New England Journal of Medicine

Image 5: The New England Journal of Medicine

Image 6: The New England Journal of Medicine

Medscape © 2023 WebMD, LLC

Any views expressed above are the author's own and do not necessarily reflect the views of WebMD or Medscape.

Cite this: F. Perry Wilson. A New (Old) Drug Joins the COVID Fray, and Guess What? It Works - Medscape - Feb 08, 2023.

Comments