This transcript has been edited for clarity. For more episodes, download the Medscape app or subscribe to the podcast on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, or your preferred podcast provider.

Todd A. Florin, MD, MSCE: Hello. I am Dr Todd Florin and I'm an associate professor at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine and director of research for the Division of Emergency Medicine at Ann and Robert H. Lurie Children's Hospital of Chicago. Welcome to Medscape's InDiscussion series on pediatric pneumonia. Today, we'll discuss the role of lung ultrasonography in the diagnosis of pneumonia. The diagnosis of pneumonia in children can be a challenging one. As point-of-care ultrasound becomes more prevalent at the bedside, studies have suggested that it can be used to evaluate for pneumonia in children saving radiation, time, and potentially cost in the acute care setting. First, let me introduce my guest, my good friend Dr Russ Horowitz, who is director of emergency and critical care ultrasound at Lurie Children's Hospital of Chicago. Welcome to InDiscussion, Russ. How are you?

Russell Horowitz, MD, RDMS: I'm doing great. Thanks so much. I love talking about ultrasound. I want to thank you for inviting me to come on.

Florin: Incredible. You're going to be an outstanding guest, Russ. What led you to your work in pediatric ultrasound?

Horowitz: I started doing lung ultrasound after doing emergency medicine. Honestly, there was a case of a traumatic event in the emergency department and we kind of went back and forth as to what was the best way to evaluate this person. I learned about the Focused Assessment with Sonography in Trauma (FAST) exam that was being done in adults all the time, but just never really bled its way into pediatrics. In retrospect, that said to me if we had been able to do the FAST exam on this patient, we could have made this diagnosis of this traumatic injury so much quicker for her. I ended up doing an emergency ultrasound fellowship and that's where my interest sort of blossomed in point-of-care ultrasound.

Florin: I love that. I think it's a real example of how you took a clinical challenge at the bedside and turned it into a professional passion to improve the outcomes of the children that we care for in the emergency department. I think that's such a great story. We've been working in the pediatric emergency department for a while, and I certainly think that the emergence of point-of-care ultrasound at the bedside has really been one of the key developments in our field over the last decade. What do you think are the most exciting changes in care that you've seen since you started practicing?

Horowitz: If we're talking specifically about ultrasound, one of the biggest differences is that people who are now coming into medical training have these ultrasound skills already. When I first started, it was a rarity for people who were in the emergency department to have point-of-care ultrasound skills. Now, a good number of med schools are teaching first-year and second-year medical students how to perform point-of-care ultrasound. We now see that as trainees come into the clinical settings, they already have those ultrasound skills. They know how to use the machine; they know how to use different types of probes and different ultrasound machines from different companies. We can adapt the clinical scenarios just like we do for their clinical training to their ultrasound skill set. If they already know how to do a cardiac setting, then they might very well be faster at absorbing that information, use lung ultrasound, and incorporate those ultrasound skills into their clinical decision-making. It honestly makes my job so much easier in teaching ultrasound because so many people are already coming in with the basic and even advanced skills.

Florin: I totally agree with that. I recently saw a really interesting piece about whether ultrasound is going to replace the stethoscope in terms of its fusion into clinical care as a diagnostic tool for us at the bedside? I don't know. What do you think?

Horowitz: I love the idea of it. I think what it really reinforces for us is that we've been using this stethoscope tool since the 1800s and we can refine a little bit of the acoustic ability, but it's truly the same thing. I think we accept its limitations, but we see it as truth. In a lot of our work, we realize that we want that auscultation ability to be better, but it just turns out it's pretty limited in what it can do for us. Ultrasound doesn't care how much you invest in terms of the money. It doesn't care about the color of your stethoscope. What it really says is, "Here's the picture," and then you have to use all of your advanced clinical skills to interpret that image and then apply that to the clinical setting. I think what we've done now is that we've made the leap, just like we have with phones and computers, to say that the technical ability is now at a very high level and we can train people to use those techniques that they know already to make their clinical care even better because we're giving them better tools to do that investigation.

Florin: Yes. I want to bring this down to a really common clinical scenario that we see in pediatric primary care in the emergency department. That is a scenario that we commonly use the stethoscope to help us make a diagnosis, and that is when a child who comes in with fever and cough. How does lung ultrasound help us in the diagnosis and management of that child who presents with fever and cough to the emergency department?

Horowitz: This is a wonderful question. When we see patients in the emergency department, their families, whether they voiced it or not, have on their mind, Does my child have pneumonia? To embrace that concern and reach across two different sides of the bed and say, "I'm going to investigate your child for pneumonia." Here's the reasons why I'm thinking about this. Of course, children are challenging, right? They're sad, they cry, they move, and they wiggle. Auscultation can be pretty challenging. Trying to hear what their lungs sound like among all those cries and all those moves is really a tough job. I think of lung ultrasound as part of how I investigate children. We know we're trying to limit their radiation exposure, so we're pretty careful about exposing them to x-rays. Lung ultrasound doesn't involve any radiation and is a tool that we use right at the bedside. If I have the question in my mind of whether this someone who I should investigate for pneumonia, then I just use the point-of-care ultrasound and investigate for pneumonia. It gives me another way for me to talk to the family, describe to them what it is that I see, and why I'm making my decisions the way I am. I don't expect that they can interpret the picture. But if I show them an area that's normal and then an area that's abnormal, whether they have experience in ultrasound or not, it becomes very clear to them as to why we're saying you do or do not have a problem.

Florin: I think that involvement of the family, of the parent and the patient, in the clinical decision-making process is super powerful and it's something that the stethoscope actually doesn't give us. We listen to the lungs. We say, "This is what I'm hearing." Parents and patients often just rely on our expertise. When you can show them a picture and show them normal vs abnormal, it really brings them into the discussion about their own disease process, their own management, in a way that is pretty cool. Kids can be squirmy, as you said. They can move around a lot. They can cry. Oftentimes, they may not want to cooperate with you. Can you talk about the actual approach? How is lung ultrasound done in children and what are the best technical approaches when you're looking for pneumonia or other findings?

Horowitz: Those are good questions. When I first started, I was probably just like most medical students, intimidated by the moving child. We look in every child's ears and that provides a challenge to us. Pediatricians get used to doing that. I think lung ultrasound is similar in that we accept that children are going to move, and we can adapt our approach to them. If we take, let's say the toddler who's somewhat unhappy, the easiest way to start, I think, is to tell the parents, "Have the child rest on you and wrap their arms around you like they're giving you a big hug." That allows me to examine their posterior chest and their lateral chest so they can move their scapula outward. That exposes their posterior chest really nicely. I take a high-frequency linear probe on each side of their back, starting high up very cranial. I just slide the probe down in what we call a lung sweep, looking at each rib interspace, right side, left side. Then you can do the flanks as the kid has their arms wrapped around the parents. That gets four out of the six areas. Then I have the parents turn the child around, raise their arms above their head. That's when they do the big cry. Then I just do those same lung sweeps in the sagittal plane down the right chest, left chest, and then we're done. The whole thing takes 3-5 minutes at most. Record those images. If the kid is really moving and it's hard for me to interpret in real-time, we have those video recordings. We just look back at them at a slower speed and then we can carefully evaluate what it is that we see.

Florin: That's great. Really, we're dealing with six lung zones: the left anterior, left lateral, left posterior, and the same three on the right side.

Horowitz: Yes. I'd like to really qualify that sometimes, when we make it very distinct, it provides this cognitive load for clinicians about where they have to look. When I think about it, I'm looking at the patient's front, sides and the back of their chest. That way I don't have to think about zone one, zone two, zone three, zone four. All I do is just think I'm doing the posterior, right and left, all the way down. Then it goes so quickly because it's very similar to the way that we listen when we're listening to someone's chest, with anterior, lateral, and posterior, both sides, and then you're done.

Florin: What are some of the features now that you would see on ultrasound that would indicate pneumonia to you?

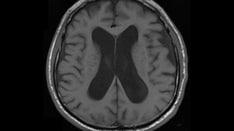

Horowitz: These are really good questions. Let's start with what normal lung ultrasound looks like. I tell people that normal lung ultrasound is very boring. What we see are horizontal lines that represents the normal lung parenchyma. Those are referred to as A-lines. I remember the A because there's a crosshatch of the A that lines up with the reverberation of the A-lines. The top of the screen is where the probe is touching the person's body. Lower on the screen is deeper into the person's body. We'll see the pleural line which slides. In the case of A-density, anything that allows the sound waves to penetrate, we now get vertical lines from the pleural line that extend all the way down. Those are B-lines. B-lines are bad. It represents that the soundwaves can penetrate. Anything that will give you more water in the lung will allow those B-lines to appear. The easiest one, I think, for people to think about is pulmonary edema. You'll have B-lines on both sides. In the case of pneumonia, we will have a small area that has some B-lines. That says to me there's a density — some water, some infection — that allows the soundwaves to penetrate. In addition, we start to see that the lung now represents what the liver looks like. That's called lung consolidation or lung hepatization, because there's a density there. We're going to use the colors black, white, and gray to help us illustrate some other features. We all remember the radiologist describing air bronchograms: little black tubes on the chest x-ray. On ultrasound, air looks like little white dots. Those are air bronchograms. and when the person breathes, those bronchograms move. So they're called dynamic air bronchograms. We now have B-lines in a focal area. We have dynamic air bronchograms, lung hepatization, and the last one is when we see a disruption of the pleural line. That's called the shred sign. It's kind of like someone takes a bite out of the pleural line. We see a hypoechoic or a gray or a black area close to the pleura. Then we see an irregular pleural line slightly deeper on the image. That's the border between the abnormal lung and the normal lung. Those are the four main findings.

Florin: That's a great summary. Russ. It feels like some of these findings may be more challenging to pick up than others. We talk about hepatization; let's say, as an example, that some of these findings may also be mistaken for other potential findings. Which are the findings that are easiest to pick up? Which are most difficult? How do we avoid some of the pitfalls that you might come across when you're doing a lung ultrasound looking for pneumonia?

Horowitz: I think the easiest things to find are the B-lines because there are these vertical laser beams that appear. They're not the best tool to tell you that the person has pneumonia just because it says that there's some sort of density. We can see B-lines with virus. We can see B-lines with other conditions as well. I consider B-lines like a tool — sort of like smoke if you're looking for fire. If you see B-lines on one area of the chest, then look a little bit medial and a little bit lateral to try to investigate for this lung consolidation. The beauty of doing point-of-care ultrasound is that you're the person holding the probe. You know where you are on the person's chest. Sometimes people ask, "Well, how do I know that that's lung and not liver?" If you're holding the probe and you're on the person's right anterior chest and you're high, then there's no liver. You can slide the probe further south, pull the liver in, and then make a comparison and see if that difference is one rib space, in which case, you're looking at liver or its many rib spaces, and that says to you that you're definitely in the thorax. That's an easy one. You highlight a very important thing, which is how do we know that we see something and it's not normal? The one area which can be a little bit more challenging than others is the left flank because we pull in stomach. Stomach has sort of a similar appearance because we have air in the stomach, and we have some sort of density. We're going to get some B- lines there, but the appearance is slightly irregular in comparison to what we see in lung ultrasound because you get to see the gastric mucosa. That does require a little bit more skill, and you have to pay particular attention to that left flank because of the stomach.

Florin: Those are all helpful tips and tricks as we help our listeners think about how to perform lung ultrasound and try to understand what the trickiest areas are when you're looking with the probe. One thing that you didn't mention, which may be worth just a brief comment, is pleural effusion. Whenever we look at a chest x-ray, we're always looking at those corners to see if there's a pleural effusion there. Certainly, if there's a larger effusion, we worry about the potential of a complicated pneumonia. Can you talk a little bit about lung ultrasound in detecting pleural effusions and where it can be most helpful?

Horowitz: Lung ultrasounds are a fantastic tool to look, particularly for plural effusions, because now, we're starting to see water or fluid around the lungs. Water appears as black on ultrasound. In that case, we can see any presence of fluid will be reflected as black on the ultrasound image. We normally don't see any black on lung ultrasound because your lungs are filled with air. That allows us to see even small amounts of pleural effusion in lung ultrasound. Although we can have the "is there fluid, yes or no" discussion, the beauty of ultrasound is we can now raise the level of this conversation to say not just, "Is there fluid, yes or no," and sometimes, x-rays have to stop at that point because they can't make further distinctions. We now can say, "Do I see within this pocket of fluid some septations? Is this now a complicated effusion?" One of the beauties of ultrasound is that I don't even always have to think of an advanced differential diagnosis. I don't even have to think the person has an effusion. You do your study. The images get portrayed for you. Then, we interpret those pictures. I really like ultrasound because it makes me look like I'm a genius doctor. People will be like, "How did you even know that was what was there?" I say, "It never was part of my thought process or initial differential diagnosis." But I chose to do the study because the person had this problem, cough, shortness of breath. Then the ultrasound gives me the answer.

Florin: We've talked about the biggest advances in medicine over time. Certainly, I think one evolution that I've seen in the time that I've practiced is the fact that CT, with all the radiation and the cost, used to be the reference standard when you had a concern for an effusion to be able to differentiate a simple free-flowing effusion from a loculated or more complicated effusion or empyema. Now, we have this tool that can be done at the bedside, where that decision can be made within a couple of minutes to be able to differentiate a simple free-flowing effusion from a loculated and complex effusion or empyema. We've really replaced the CT scan with ultrasound as the reference standard for discriminating between those findings in kids with pleural effusion, which I think has been a major advance in this in this space. We were talking a little bit about the pitfalls and the challenges of ultrasound. Now, we should probably move into a discussion of accuracy. How accurate is lung ultrasound in diagnosing pneumonia? It's a challenge because we do know that chest radiography is really not a great gold standard. In fact, it's more like a bronze standard at best, with some challenges in interrater reliability and challenges in interpretation. How accurate is lung ultrasound?

Horowitz: I love that you pointed out that chest x-ray isn't as good as we wish or hope or think it is. A lot of the studies for the most part, have compared ultrasound to chest x-ray. But as you describe, chest x-ray is slightly imperfect. Ultrasound has given us sensitivities and specificities in the areas of low- to mid-90s: 93, 95, 96. That seems to be the meta-analysis consensus. Those studies provide me a lot of comfort in using ultrasound to help to make that diagnosis. I would also like to highlight a few things specifically as we think through the possibility of pneumonia that often gets reported on chest x-ray. The thing that is somewhat infuriating to us as practitioners is when we get a result that can't distinguish between atelectasis and infiltrate. It used to bother me more until I realized that the radiologist is limited by their ability because they're being given a static image and they can't tell if things are changing with respirations. Ultrasound can distinguish between atelectasis and infiltrate. In a way, ultrasound is better than chest X-ray because we get to see the person breathe and we can see if these air bronchograms change as the person breathes.

Florin: Is that one of the ways to distinguish between atelectasis and consolidation on an x-ray, static vs dynamic air bronchograms? How difficult is it to make that distinction?

Horowitz: Yes, that is one of the critical features. I described the little black tubes that we see on chest x-ray, air bronchograms, but they can't tell us whether those move or change as the person breathes. On ultrasound, we see these chains of little white dots. Some people say it looks a little bit like coins that someone would throw up into the air. In that case, we have dynamic air bronchograms that will move and change as a person breathes. That's pneumonia. Those little chains of white dots don't move as the person breathes. Those are static air bronchograms. Those are atelectasis. I must admit, even though I describe it as being very distinct and somewhat apparently easy, that's hard. But with a little bit of attention, you can really look carefully. Even if the child moves, we've recorded this image. You would just play that image back and evaluate whether you're seeing these little chains of white dots move over time.

Florin: That is really helpful to think about. I do want to go back to the sensitivities and specificities that you quoted a little while ago. Low- to mid-90s for chest ultrasound is what the meta-analyses come up with. I do think it's worth mentioning an important caveat with regard to those meta-analyses is that all of these studies that were in these meta-analyses in children compared chest ultrasound to our bronze or nickel standard of chest radiography. They really were not being compared with a super strong reference standard. There have been a couple of smaller studies that have compared chest x-ray and chest ultrasound to chest CT. I'm wondering if you might want to talk about those results a little bit.

Horowitz: Those results are exciting, but we recognize that the vast majority children don't and shouldn't get chest CT's. The children represented in the meta-analyses are sicker children. The results are very similar and even more exciting from my ultrasound perspective, in that we see that the ultrasound is about as good as chest x-ray. I am being as general as I can because they're somewhat limited. Sometimes [it is] even better at identifying the presence of pneumonia and distinguishing between pneumonia and atelectasis. It provides me a lot of comfort, but I recognize that we're probably not going to get a lot more of those studies just because we're reducing the amount of radiation that we expose the children to.

Florin: Those are challenging studies to do for sure. I don't think that we will be seeing more of those studies. When I think about the next series of studies that need to happen in this space, it really is about clinical outcomes. There have been a ton of studies now that have done these comparisons to chest ultrasound to chest x-ray and a few of them that have looked at the CT standard. But not a lot of these studies have looked at the clinical course of children with certain findings on ultrasound, and the degree of those findings on ultrasound. I feel like that's where the field is going to go. How do we predict the outcomes of these kids based on their lung ultrasound findings? The holy grail for pediatric pneumonia is can we differentiate bacterial from viral infection? Can we determine which kids require antibiotics and in which kids we can safely avoid antibiotics? I'm curious whether there is a way to determine etiology of pneumonia based on these ultrasound findings? Can we use ultrasound to help us with our antibiotic decision-making?

Horowitz: This is a really good point. It reminds me of when I first learned pediatrics. Any effusion you saw in someone's ear was an ear infection, and they all got antibiotics. As we got smarter, we realized that the vast majority of ear infections are going to go away and are related to virus. I think this mindset of just because someone has an infiltrate on x-ray or ultrasound, it doesn't necessarily mean that it's bacterial. Your question goes to can we use this better tool to help us identify the difference? I think we're pretty good at two ends, but we're pretty limited in terms of what the utility so far has shown us about lung ultrasound. For sure, small subpleural consolidations, less than about 1 cm, aren't pneumonia. We see these in conditions like COVID. We saw them in H1N1. We see these in bronchiolitis. Subpleural consolidations bigger than 1 cm are pneumonia. Some work has said, "Well, maybe we should start to talk a little bit more about the size of these infiltrates, and maybe bigger sizes represent that it is more likely to be bacterial and slightly smaller sizes are more like to be viral." Those studies are pretty limited, and I think we're just not there yet. My hope is that there's going to be something that we find in something that we see: size, quality, characteristics that are going to put us even more firmly in certain camps so that we limit the radiation exposure of children by x-raying them and limit the antibiotics exposure by being able to use ultrasound to make this distinction.

Florin: This has been great, and I agree that is the fundamental challenge. I also think that is where ultrasound has great potential as we manage these kids who present with respiratory complaints. Russ, this has been awesome. It's always great chatting with you about this topic. I know that we can spend hours on it, but it's been great to have you join us in this discussion about lung ultrasound and have you share your expertise. I greatly appreciate it.

Horowitz: Thanks very much, Todd. I appreciate it. Any chance to talk about ultrasound brings me joy.

Florin: That is wonderful. That's a great way to close. Today we've talked with Dr Russ Horowitz about lung ultrasound in the diagnosis of pediatric pneumonia. I want to bring up a few takeaways for you. First, auscultation with a stethoscope can be challenging in young children because of crying and their limited ability to cooperate with the exam. We would like to limit radiation exposure and really only use antibiotics when necessary. Point-of-care lung ultrasound offers us the opportunity to investigate for pneumonia in a quick and accurate way at the bedside in a way that also involves parents and patients in the diagnostic process. In terms of the ability to get the ultrasound done, using lung sweep methods, sweeping in six zones — three on the right, three on the left of the anterior, lateral, and posterior. The four key sonographic findings that we're going to expect in pediatric pneumonia on lung ultrasound are lung consolidations greater than 1 cm, which can look like liver or hepatization of lung, three or more B-lines in a focal area of the lung, dynamic air bronchograms, and the shred sign. With that, thank you for tuning in. If you haven't done so already, please take a moment to download the Medscape app to listen and subscribe to this podcast series on pediatric pneumonia. This is Dr Todd Florin for InDiscussion.

Resources

Focused Assessment With Sonography for Trauma

Dynamic Air Bronchogram and Lung Hepatization: Ultrasound for Early Diagnosis of Pneumonia

Lung Ultrasound for the Diagnosis of Pneumonia on Adults: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

Can Lung Ultrasound Differentiate Between Bacterial and Viral Pneumonia in Children?

Follow Medscape on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and YouTube

Medscape © 2023 WebMD, LLC

Any views expressed above are the author's own and do not necessarily reflect the views of WebMD or Medscape.

Cite this: Point-of-Care Lung Ultrasounds: The Role of Lung Ultrasonography in the Diagnosis of Pediatric Pneumonia - Medscape - May 04, 2023.

Comments