This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Robert D. Glatter, MD: Welcome. I'm Dr Robert Glatter, medical advisor for Medscape Emergency Medicine. Joining me today to discuss the recent 2023 Match results for emergency medicine, and their impact, is Dr Robert McNamara, professor and chair of emergency medicine at Temple University and also past president of the American Academy of Emergency Medicine (AAEM). Also joining me today is Dr Amy Faith Ho, senior vice president of clinical informatics and analytics at Integrative Emergency Services in Dallas, Texas.

Welcome to both of you. Thanks so much for joining me today.

Amy Faith Ho, MD, MPH: Thanks so much for having us.

Glatter: I want to begin our discussion on the high number of unmatched emergency medicine spots: well over 550 in 2023, up from 219 in 2022. The concern is that, even a year prior, there was only a handful, I think — 13 or 14 unmatched positions.

Bob, I'm going to begin with you. Let's talk about the reasons for the increase and what you see as the main factors behind this increase in spots that were unmatched this year.

Robert McNamara, MD: I think it's a twofold issue. First off, we didn't have a great year last year. The SOAP [Supplemental Offer and Acceptance Program] filled most of the spots, but we also had a historically high number — until this year — of unmatched spots last year.

The best source would be to talk to the students, right? We don't have them here, but I think most are settling on a twofold thing. One is just the raw economics: Am I going to have a job? That's multifactorial. There are two key issues there. One is that 2 years ago, the class graduating amidst the pandemic had difficulty finding jobs that weren't filtered out. That was because ED volumes went down and places weren't sure they wanted to hire. Then, on top of that, there was a study published by the American College of Emergency Physicians (ACEP) that said we're going to have an oversupply coming in 2030 of 9600 excess emergency physicians.

The second thing, which to me is way more concerning, is the burnout. Right now, we are leading in burnout at 65%. In the most recent survey, we were 5% above everybody else.

I believe there have been many factors contributing to that, some of which have existed for a long time, like the boarding problem that is getting worse again. As you know, many physicians with the American Academy of Emergency Medicine (AAEM) think the corporate influence has really been a problem. People see that; they feel loss of autonomy in their jobs and are concerned that corporations will replace them with nonphysicians. I think it's a twofold thing.

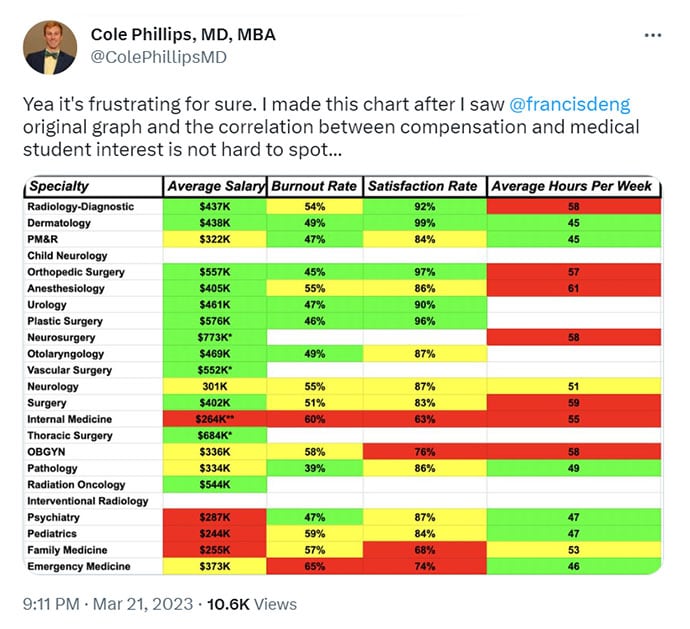

Glatter: Exactly. Amy, I want to bring you into this. A tweet of yours homes in on what Dr McNamara is talking about — that this situation is not unique to emergency medicine; it has happened with family medicine, psychiatry, and pediatrics.

I'll let you elaborate on this and expand a little bit on what your thoughts are in these primary care "safety net" specialties.

Ho: There are a couple of issues here. One is absolutely that you see the safety-net category of specialties going down in popularity. Emergency medicine is obviously the one that we're all in so that's the one that we are focusing most on. Family medicine and pediatrics going down is also highly concerning.

I think this reflects a couple things. One is just, frankly, a generation of medical students that understand work-life balance. I think they were forced into that because, as you saw COVID-19 evolve, this was the first time, I think, that doctors had to balance their work life with, literally, their personal lives. Go back to March, February, April of 2020, and there was a huge concern when these kids were in medical school that ER doctors and frontline doctors were bringing COVID back to their families, potentially getting elderly parents that live with them sick, and potentially sacrificing their own lives.

I think that forced this generation of trainees to think, What does work mean to me? The conclusion is that they don't want to be martyrs for the job, which is what medicine universally felt like.

If you take this category of people who understand work-life balance and you put them into choosing specialties — Dr McNamara commented on this already — you have two pieces; There is the benefit — what you want to do with your life and the reimbursement and compensation for it, and there's what you're willing to sacrifice.

With everything going on in medicine, there's a high amount of burnout, mostly because of moral injury, like systemic failings in the healthcare system. Then you also have this substantial drop in reimbursement and pay. CMS is cutting RVU reimbursements right now. Health insurers are getting more powerful and actually denying claims so that providers aren't getting paid.

At the same time, there's a scope-creep issue of advanced practice providers (APPs) getting traded in one-for-one for doctors by contract management groups that don't really understand the difference between a doctor and an APP. All of this put together makes these safety-net specialties highly unattractive to medical students, which is unfortunate because that's really where we have needs in our healthcare system.

Glatter: I completely agree with you. These are very important points you make.

Bob, the APP issue has been front and center with the concern that 1 in 5 patients will be seen or were to be seen by an APP in some sense.

This happened in the house of anesthesia 40 years ago, where there was a lack of spots for many years. Then they self-corrected by increasing the number of spots over the years.

We need to work with our APPs because they're valuable to our team. What do you see as the pathway to incorporate them in the next several decades?

McNamara: The factors are a little different in emergency medicine in the use of nonphysician providers. A recent article published in the past couple of months showed some information from the industry, Envision, and American Physician Partners, where they basically said, "We want to use the cheapest resource to get the job done. We'll gladly replace you with a physician if it's going to be more for the bottom line."

We have to understand that this is private equity that's running a large swath of emergency medicine. Their duty is to the investor, not to the patient. We've allowed this influence into our specialty and there's the great concern that they're just going to replace you unless you can show that you're cost-beneficial.

Now, there's a whole movement here where Physicians for Patient Protection, which is really pushing back on the whole idea. To me, we've all made position statements. The AAEM has, the college has. Those are all paper tigers. It's the person who owns the contract that decides the staffing. We need to hone down on making sure it's the physicians that decide the mix that's going to see patients.

Most of the people who applied for emergency medicine are not in it for the money. They have a strong sense of social justice and they know they are going to make a decent dollar, but the main two figures are: Will I have a job and will I survive in it? Will I burn out in a corporate world while I'm trying to serve the neediest of society and being pushed for metrics?

Glatter: The lack of autonomy really tugs at us in what's happened. The issue of the right fit for medical students over issues such as prestige and ability to make money — there has to be a reset, in my mind. It's a cultural shift in teaching medical students to understand themselves and where their passions are.

Ho: I agree with that. Medicine is an incredibly noble profession, no matter how you slice it and no matter what specialty you're in. My belief is that you should pick something to do with your life that really drives you. I think there are definitely realities, which we're talking about here, of what you need to do to sustain your life, your lifestyle, your debt, and so on.

Culturally, this is a group of young people (eg, trainees and medical students) that understand the work-life balance. When you look at some of the things that make it less balanced (ie, compensation), I agree with Dr McNamara. I don't think ER doctors are going into it for the money. They have obvious needs and they need to make a career. There is a feeling of more insult when reimbursement cuts. I don't think it's actually the dollar amount that's getting us; it's the feeling of, "Hey, we went through a pandemic, we work harder than we ever did before, we are doing acrobatics to make things work."

A great example of this is waiting-room medicine. The ER has largely shoved out into the waiting room and come up with processes to see patients out there to address issues like boarding that are interdisciplinary and long-term solutions that we're working on. In the meantime, we've taken on the short-term patch to make this safe, to be there for our patients. When you balance that with the feeling of, "Hey, we're unappreciated and CMS doesn't recognize this," that's where you start to run into the dissatisfaction.

Again, I agree. I don't think it's the actual dollar amount. I think you see this with family medicine and pediatrics. Their administrative burden is going up. Those are some of the lower-paid specialties. They're squeezed into 6- to 10-minute visits for very complicated patients. They're charting after work for hours. They're feeling the squeeze and the lack of appreciation.

Where you see that field going is actually interesting. You see many trends about direct primary care, where they're trying to cut out middlemen so that they can treat patients the way they want to treat patients. Unfortunately, in that model, it doesn't necessarily address the underserved and patients who can't fall into that business model, but you see many market forces shaping how doctors are trying to deliver care.

Glatter: I want to go back to the issue of boarding because much of this stems from, essentially, a workforce shortage. We're talking about nurses upstairs in the hospital where we can't send our patients who are admitted upstairs. We're recovering from this very slowly.

The issue of locums replacing a large number of team-based care up on floors, ICUs, even in the emergency department, has played a role not only in cohesiveness but in terms of patient outcomes.

Boarding — we thought we had a bit of a handle on it maybe in the past 5 years or so but now it has really cascaded. Attracting the students we want to attract, but having to play waiting-room medicine and dealing with boarding are two of the biggest things that I think students look at.

McNamara: I agree with you. We all know that emergency medicine is an inherently stressful specialty. It's not just what we see: the violence, the opioid epidemic, the 24/7, and the nights, weekends, and holidays. We have a baseline. You're walking into it, it's going to be stressful, and it doesn't matter what the salary is. If you feel that somebody's taking advantage of you, whether it's the contract holder who you think is taking money out of your pocket; or CMS, which is not appreciating you; or the hospital that is not giving you the resources, that's going to erode your core.

Boarding is a huge crisis, and you have a specialty that's afraid to speak up as well. We're afraid to speak up for fear of losing our jobs, and that's a very uncomfortable situation.

You want to stand up and advocate about boarding. I complain about boarding all the time. I speak to the CEO of the hospital. I just sent him a note 2 days ago when I worked a Monday shift and we were getting admissions upstairs in less than 2 hours, which was remarkable — like, "Good job! Let's keep this going." In most places, we can't do that. It creates that situation where you're doing waiting-room medicine. The same patients are staying there, shift after shift. You need to see the new patient to be educated as a student or resident.

It's not just in the hospital. The nursing homes can't take patients because they don't have staff. The hospitals say, "Well, we're backed up; we can't clear the beds because the other places have lost workforce."

Glatter: How do you incentivize the system to work to solve this problem?

Ho: This is a really interesting discussion, especially when we're talking about boarding and waiting-room medicine. I actually deviate a little bit from Dr McNamara's point here. I absolutely think that boarding is a huge issue. There are advocacy efforts between ACEP, AAEM, and so on that share stories of boarding to try to help people understand why this is such a large issue. We know that it's heavily interdisciplinary, right? There's the question of, why do Americans need the ER so much? That's a safety-net question. That's a healthcare access question.

Once you're in the hospital, there are questions of staffing for nursing, labs, and radiology. There are also questions of, where do patients that are in the hospital go (ie, skilled nursing facilities, long-term care)? What are the insurance approvals for moving patients there? What's the speech therapy, OT, and PT that needs to happen? It's highly interdisciplinary.

Where I deviate from Dr McNamara is that I feel like holding patients hostage for us to stomp our feet and say, "This is an issue" is not the solution. I don't think us refusing to go into the waiting room is the right solution. I think we, as physicians, need to lead the processes that can make waiting-room medicine a little safer.

The reason I say that is based on looking at everything we do in the ER. If the glide scope is broken, I'm ready with DL [direct laryngoscopy]. If there is no bougie, maybe I'm ready to use a fiberoptic or digitally intubate or something like that. We have many fail-safes of taking very imperfect situations and making them manageable. That's how I see waiting-room medicine because I think we should create processes to make it manageable so that we can see patients while we're working on the long-term solution.

The long-term solution is absolutely where we need to drive forward, but without us being willing and able, and putting our full capacity behind keeping patients safe now, we're really just complaining. We have to be part of the solution and we have to entrench ourselves really deeply, especially in that short-term solution, because we're so close to the patient.

McNamara: The problem is we're enablers. We do everything we can for our patients. That's the nature of emergency medicine. We are willing to see people in the waiting room, in chairs, in hallways. We will do that because that's part of the moral fiber of an emergency physician.

The problem is that people know and take advantage of that. Comparing us with other specialties, would they accept, "Hey, we need you to do the operation, not in the OR but here in the hallway." This is not going to happen. It's a balance. Obviously, we're all committed to the patient first, but there has to be an awakening.

There was a great New England Journal of Medicine editorial. Gabor Kelen, MD, was one of the authors. It really outlined the problem: The more waste, more boarding, the higher the morbidity and mortality. It's a self-perpetuating situation.

I don't really know the solution. We need a public outcry. We need somebody to say, "This isn't right." Now, that can happen in your individual institution. We've been able to, with the strength of our department in our school, argue and continually press the issue, and work with other colleagues.

I actually rounded on the inpatient units with some other chairs to say, "How can we make things go faster up here?" That's not what you get if you're working in a community hospital where your boss is private equity. You're not going to be able to press that button, and it's creating a big problem in our specialty.

Glatter: Penalizing hospitals that have longer boarding times in the ED — certainly there have been readmission criteria from CMS that have looked at congestive heart failure and other outcomes and readmissions. Why not create a system where boarding is made front and center? We have a national task force to address this and penalize systems that can't accommodate and adjust to this ongoing issue.

Ho: It's actually a really interesting idea. There's certainly a point to bringing it front and center and making it a metric. There is a danger there, though, that when you incentivize it with a CMS metric or something, you come up with the wrong solutions.

Remember that this is a very interdisciplinary question. It's even a societal question of, what do we do with patients who are debilitated from an acute stroke or something that requires inpatient hospitalization? What do we do with them if they have no family or no insurance? It opens up many questions of what kind of safety net is there in our social fabric. Much of that's legislative.

Putting in a new metric maybe isn't the solution without forcing many of those conversations, and bills, really, about how to create support in society for these patients who end up being quite long-term stayers in the hospital, because that will improve much of the throughput.

The same is true for workforce shortages. What can we do here to help incentivize nursing? Should you cap locums' pay because nurses and physicians sometimes also will go chase way higher dollars than locums? I absolutely make it front and center, get some information, get some data out there so we know what's there. For me, just throwing a metric and incentive pay behind that, or a penalty, may or may not have downstream effects as people learn to just game that system.

Glatter: When it's linked to patient outcomes, that really is the bottom line here, when you look at the outcomes we know are adverse with longer boarding times.

Getting back to the crux: What does 2024 hold for the Match, and 2025 and 2026? Looking at the surplus, Dr Marco's article, are we headed on a trajectory where we're going to see 1000 unmatched spots going forward?

Ho: My opinion is that some of the issues we talked about here (the moral injury, systemic issues, reimbursement, pay, and the culture of work-life balance) are not going to get better, especially not in time for 2024. Again, those medical students still live through COVID-19. As long as the trainees go through this COVID-19 time, it will continue to worsen without any significant interventions (eg, multidisciplinary, from the specialty societies, reimbursement, from hospitals). Unfortunately, we might increase our unmatched spots and/or not fill them in the SOAP.

Glatter: The attrition rate will certainly be going up. From what I can tell, things are not improving.

McNamara: You mentioned the attrition rate. After the Marco study, the Gettel study came out. The Marco study was based upon a 3% attrition rate. The Gettel study said, "Well, we actually have a 5% attrition rate," so it throws off all the figures of that projected 9600.

The unfortunate thing is realizing, wait a second — we've got a 5% attrition rate? When I was younger, we were worried that it was 1.5% attrition. That's a reflection of the problems we are seeing within the specialty. We have to wake up and say that we're the highest in burnout. The professional societies need to look at the issues. Obviously, I have my biases and think a large part of it is the feeling of being taken advantage of by corporate entities and whatnot.

Emergency medicine, in its purest form, is still the greatest specialty, in my view. I've had a great career, but I've not been in a situation where I felt like I was taken advantage of or I couldn't advocate for my patients.

Now, we know there are going to be more residency slots next year because we're containment-approved programs. I don't think we're going to get much worse, but I don't think we're going to get much better.

The pool itself is my greatest concern — that the best and the brightest, and I think it's already happened this year, have decided to go somewhere else. We're filling huge numbers with the SOAP. Some of them are going to be real high-quality people who didn't match in ENT or whatever but are in love with emergency medicine; they just didn't apply to us first. You have to be in love with the specialty these days to survive in it.

There are many jobs because our attrition rate is high. It's basically diluted the pool. There were data in the past: 20% were in the top 10% of the class, two thirds were in the top one third of the class — like, the best and the brightest were choosing emergency medicine. I don't know what it's going to be now. I also know that if you're filling in the SOAP, you're not getting people whose first choice was emergency medicine.

That's going to affect the patients because it's going to be difficult to bring the best person to the bedside if it's "I fell into the specialty through the SOAP and I don't really like it."

Ho: I actually take a slightly more optimistic view. I still think that the Match is probably going to get worse next year for emergency medicine, but I think it's not that we're not getting the best and brightest. The people we are getting are intensely passionate about emergency medicine despite all the issues. What that means is you get a class that has a large amount of diversity, many different backgrounds, especially ones in social equity, because they're really interested in this idea of being the safety net. They know that emergency medicine is absolutely a safety-net specialty, one that's being really rained on in many ways because of things going on in the world.

Even in the SOAP, you're maybe getting people who didn't have the best scores or the best GPAs. Let's be honest: Those were never great indicators of how good or how compassionate of a bedside doctor you are.

What I think is happening, even with the SOAP, is that the diversity we are bringing in (ie, students from various backgrounds) for the specialty will really help the specialty move toward an area of advocacy. For that, I'm extremely optimistic about the new generation who, again, understands work, understands life, understands the issues in healthcare when they're getting in vs some older classes that went in because of that and maybe didn't understand the complexities of the healthcare system. For that, I am extremely thrilled to meet the new class.

Glatter: I want to thank both of you for a lively discussion with important points that you both brought up. Thank you again.

Robert D. Glatter, MD, is an attending physician at Lenox Hill Hospital in New York City and assistant professor of emergency medicine at Zucker School of Medicine at Hofstra/Northwell in Hempstead, New York. He is an editorial advisor and hosts the Hot Topics in EM series on Medscape. He is also a medical contributor for Forbes.

Amy Faith Ho, MD, MPH, is an emergency physician, published writer, and national speaker on issues pertaining to healthcare and health policy, with work featured in Forbes, Chicago Tribune, NPR, KevinMD, and TEDx.

Robert McNamara, MD, is professor and chair of emergency medicine, and chief medical officer at Temple University in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

Follow Medscape on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and YouTube

Credit:

Image 1: Cole Phillips, MD, MBA on Twitter

Medscape Emergency Medicine © 2023 WebMD, LLC

Any views expressed above are the author's own and do not necessarily reflect the views of WebMD or Medscape.

Cite this: Robert D. Glatter, Robert McNamara, Amy Faith Ho. Has Emergency Medicine Residency Lost Its Appeal for Good? - Medscape - May 16, 2023.

Comments