This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Matthew F. Watto, MD: Welcome back to The Curbsiders. Today we're going to be talking about acute pain in the hospitalized patient with opioid use disorder (OUD). This is a condition that has always terrified me. I feel like now I'm starting to know what to do.

Paul N. Williams, MD: We talked about this a lot back when we were training in the days of leeches and trephining. It was much more challenging. Today we actually have tools to do a better job of managing addiction.

Watto: Let's give the audience some tips we learned from Dr Shawn Cohen. People often use the term "opioid use disorder" as though the patient is just withdrawing, it's not life threatening, don't worry about it. And while it's not like alcohol withdrawal, and the patient isn't necessarily going to die from opioid withdrawal, Dr Cohen made the point that untreated opioid withdrawal and acute pain are actually life threatening because they can lead to premature hospital discharge.

So, addressing pain in the patient with OUD is critical. It's a very patient-centered thing to do, and it should be the standard of care, because if someone is leaving the hospital with endocarditis, that is life threatening. We really need to treat their pain and their withdrawal, and keep them in the hospital when indicated.

Don't Stop OUD Treatment

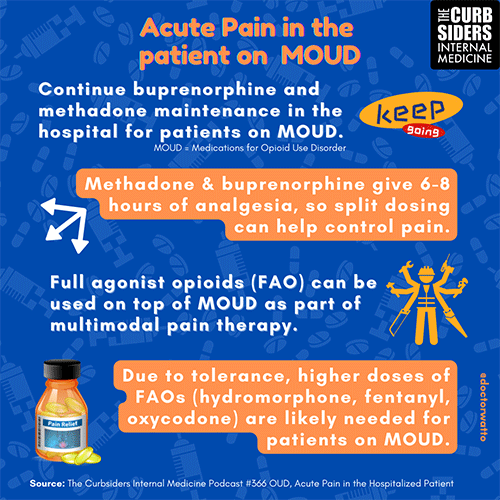

Watto: If the patient is on a medication for OUD (such as methadone or buprenorphine), should we continue those drugs? We might need to give them something more for pain. Can we give pain meds on top of methadone or buprenorphine?

Williams: This is a great question that comes up a lot. The short answer is yes, we should continue the patient's OUD treatment. There's always some confusion about precipitating withdrawal by giving full agonist therapy on top of partial agonist therapy because the mechanism can be a little bit counterintuitive.

If the patient is already on buprenorphine, it's totally fine to add full agonist therapy. The pain medication may not be as efficient when the patient is taking buprenorphine, but it will still break through and hit the receptors it needs to hit. You may need to give a higher dose and you may need something that has a stronger affinity for those receptors. But you should continue their medications because when they no longer have the acute need, you won't have to deal with the transition back to buprenorphine or methadone. It's already riding there to prevent the withdrawal symptoms. It's both elegant and humane to continue those OUD medications.

Watto: You mentioned prescribing something with a higher potency (such as hydromorphone) on top of buprenorphine because morphine has a really strong affinity for the receptor. Methadone is a full agonist itself, but once-daily dosing of either buprenorphine or methadone has a long-term effect on opioid cravings, but not a long-acting effect on pain. Treating pain in these patients is always going to be multimodal, but sometimes acetaminophen and other NSAIDs alone are not going to get through. You might need to give full-agonist hydromorphone or oxycodone on top of their OUD treatment.

So please don't stop the methadone or buprenorphine that the patient is already taking. If you want to get fancy, you can split them up into three- or four-times-daily doses because they do have 6-8 hours of analgesic effect. But don't stop them when the patient comes into the hospital.

Williams: Patients deserve to have their pain treated. A history of OUD should not be a consideration. Regardless of whether they are on medication for OUD or not, patients who need full-agonist therapy should be receiving it. It's just not humane to not give it. That's a gentle reminder that the presence of background OUD is not a contraindication for opioid use in the acute setting because sometimes opioids are needed for pain relief.

When Fentanyl Is on Board

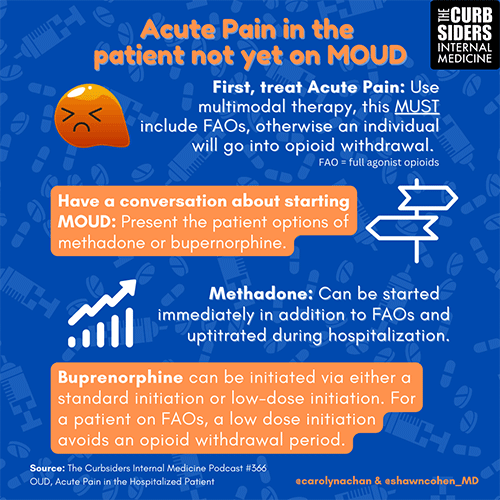

Watto: Let's say the patient has recently taken fentanyl but is not on either buprenorphine or methadone. Now the patient is starting to go into withdrawal. That's a more complicated situation. Should we give them full-agonist opioid therapy to prevent withdrawal? Can we do that?

Williams: You're angling for a yes, and that is correct. I would also say it's one of those situations where it depends. On the podcast, we presented two different scenarios. In one, the patient was having mild discomfort and there was a chance to have a conversation about transitioning to a treatment for OUD.

In the second scenario, the patient had significant pain that needed to be addressed urgently. In that case, the patient should receive full-agonist therapy. You can have a discussion about treatment of the OUD at another time. There are times to do it and times not to. In the setting of acute pain, especially severe pain, that's probably not the time patients are most interested in talking about outpatient management of their OUD.

Watto: If the patient with mild pain has used fentanyl and can get by for a while, you might be able to wait until the fentanyl is out of their system and then give them buprenorphine at the standard dose. But if the patient has moderate to severe pain, you will need to give them something for pain right away. Methadone can be given immediately, and it doesn't precipitate withdrawal the way that buprenorphine would if the patient still had fentanyl in their system.

If you're going with methadone, it's a bit more straightforward: Give 30 mg as a first dose and go from there. But if you want to start buprenorphine or if the patient is already on it, you really have to give them a full agonist for pain in the near term until the fentanyl is out of their system. You can initiate treatment slowly with low-dose buprenorphine and gradually build up the dose while continuing a full agonist for pain (such as hydromorphone). We even talked about using hydromorphone PCA in some cases.

This stuff was also new to me, Paul. But it really does work and the patients are so grateful when they're able to stay in the hospital and get care. It's a much better experience for them overall than what they're used to. For me, that's one of the most gratifying things about practicing addiction medicine and treating patients in the hospital. Any final thoughts on this?

Williams: I agree. If you can avoid being part of the patient's ongoing trauma, that's always a good thing. And if you can do anything to repair trust and engage and be a positive part of the patient's life, it's an amazing opportunity to do so.

Watto: We get into all of the nitty-gritty details on this topic on the episode Opioid Use Disorder and Acute Pain in the Hospitalized Patient.

This has been another episode of The Curbsiders, bringing you a little knowledge food for your brain hole. Until next time, I'm Dr Matthew Frank Watto.

Williams: I remain Dr Paul Nelson Williams. Thank you and goodbye.

Follow Medscape on Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, and YouTube

Credits:

All images: The Curbsiders

© 2023 WebMD, LLC

Cite this: Matthew F. Watto, Paul N. Williams. Opioids on Top of Opioids: Treating Acute Pain in Patients With OUD - Medscape - Mar 10, 2023.

Comments