Abstract and Introduction

Introduction

U.S. drug overdose deaths increased 30% from 2019 to 2020 and 15% in 2021, resulting in an estimated 108,000 deaths in 2021.* Among persons aged 14–18 years, overdose deaths increased 94% from 2019 to 2020 and 20% from 2020 to 2021,[1] although illicit drug use declined overall among surveyed middle and high school students during 2019–2020.[2] Widespread availability of illicitly manufactured fentanyls (IMFs),† proliferation of counterfeit pills resembling prescription drugs but containing IMFs or other illicit drugs,§ and ease of purchasing pills through social media¶ have increased fatal overdose risk among adolescents.[1,3] Using CDC's State Unintentional Drug Overdose Reporting System (SUDORS), this report describes trends and characteristics of overdose deaths during July 2019–December 2021 among persons aged 10–19 years (hereafter referred to as adolescents). From July–December 2019 to July–December 2021, median monthly overdose deaths increased 109%, and deaths involving IMFs increased 182%. Approximately 90% of overdose deaths involved opioids, and 83.9% involved IMFs; however, only 35% of decedents had documented opioid use history. Counterfeit pill evidence was present in 24.5% of overdose deaths, and 40.9% of decedents had evidence of mental health conditions or treatment. To prevent overdose deaths among adolescents, urgent efforts are needed, including preventing substance use initiation, strengthening partnerships between public health and public safety to reduce availability of illicit drugs, expanding efforts focused on resilience and connectedness of adolescents to prevent substance misuse and related harms, increasing education regarding IMFs and counterfeit pills, expanding naloxone training and access, and ensuring access to treatment for substance use and mental health disorders.

Funded jurisdictions entered data from death certificates, postmortem toxicology testing, and medical examiner or coroner reports into SUDORS for both unintentional and undetermined intent drug overdose deaths. Monthly trends in all overdose deaths and deaths involving IMFs**[4] among decedents aged 10–19 years during July 1, 2019–December 31, 2021 and percent change in the median number of monthly deaths, comparing subsequent 6-month periods, were calculated among 32 jurisdictions.†† Percentages of overdose deaths were calculated by demographic characteristics and drugs involved in 47 jurisdictions,§§ and by circumstances in 43 jurisdictions,¶¶ overall and for decedents within two age groups: 10–14 years and 15–19 years. Analyses were performed using SAS (version 9.4; SAS Institute). This activity was reviewed by CDC and conducted consistent with applicable federal law and CDC policy.***

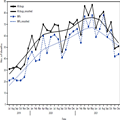

During July 2019–December 2021, a total of 1,808 adolescent overdose deaths occurred in 32 jurisdictions with available trend data. The number of monthly overdose deaths increased 65% overall, from 31 in July 2019 to 51 in December 2021, peaking at 87 in May 2021 (Figure 1). The number of deaths involving IMFs more than doubled, from 21 to 44 during this period, peaking at 78 in May and August 2021. Median monthly overdose deaths among adolescents increased 109%, from 32.5 during July–December 2019 to 68 during July–December 2021; during the same period, deaths involving IMFs increased 182%, from 22 to 62. Median monthly deaths increased during each 6-month period from July–December 2019 through January–June 2021 and decreased during July–December 2021 but remained approximately twice as high as during July–December 2019.

Figure 1.

Number of drug overdose deaths and deaths involving* illicitly manufactured fentanyls† among persons aged 10–19 years (N = 1,808), by month — State Unintentional Drug Overdose Reporting System, 32 jurisdictions,§ July 2019–December 2021¶

Abbreviations: IMF = illicitly manufactured fentanyl; SUDORS = State Unintentional Drug Overdose Reporting System.

*A drug was considered involved if it was listed as a cause of death on the death certificate or medical examiner or coroner report.

†Includes IMF and fentanyl analogs, which were identified using both toxicology and scene evidence because toxicology alone cannot distinguish between pharmaceutical fentanyl and IMFs.

§Alaska, Arizona, Colorado, Connecticut, Delaware, District of Columbia, Georgia, Illinois, Kansas, Kentucky, Maine, Massachusetts, Minnesota, Missouri, Montana, Nevada, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New Mexico, North Carolina, Ohio, Oklahoma, Oregon, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, South Dakota, Tennessee, Utah, Vermont, Virginia, Washington, and West Virginia. Illinois, Missouri, and Washington reported deaths from counties that accounted for ≥75% of drug overdose deaths in the state in 2017 per SUDORS funding requirements; all other jurisdictions reported deaths from the full jurisdiction. Jurisdictions reported deaths for all 6-month periods from July 2019 to December 2021.

¶Overdose deaths were smoothed using locally weighted smoothing. The smoothing parameter with the lowest Akaike information criterion was used.

During July 2019–December 2021, among 2,231 adolescent overdose decedents in 47 jurisdictions with available data, more than two thirds (69.0%) were male, and a majority (59.9%) were non-Hispanic White persons (Table). Overall, 2,037 (91.3%) deaths involved at least one opioid; 1,871 (83.9%) involved IMFs, and 1,313 (58.9%) involved IMFs with no other opioids or stimulants. Approximately 10% of deaths involved prescription opioids, and 24.6% involved stimulants. Ninety-three (4.2%) deaths involved neither opioids nor stimulants.

Among 1,871 overdose deaths in 43 jurisdictions with available data on circumstances, 1,090 (60.4%) occurred at the decedent's home. Potential bystanders††† were present in 1,252 (66.9%) deaths, and 1,089 (59.4%) decedents had no pulse when first responders arrived. Among deaths with one or more potential bystanders present, no documented bystander response was reported for 849 (67.8%), primarily because of spatial separation from decedents (52.9%) and lack of awareness that decedents were using drugs (22.4%). Naloxone administration was documented in 563 (30.3%) deaths. Approximately one quarter of deaths had documentation of ingestion (23.8%), smoking (23.5%), and snorting (23.0%); evidence of injection was documented in 7.8% of deaths. Evidence of counterfeit pills was documented in 24.5% of adolescent deaths. Thirty-five percent of adolescent decedents had documented opioid use history, and 14.1% had evidence of a previous overdose; 10.9% had evidence of substance use disorder treatment, and 3.3% had evidence of current treatment. Approximately 41% of decedents had documented mental health history, including mental health treatment (23.8%), diagnosed depression (19.1%), or suicidal or self-harm behaviors (14.8%) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Mental health conditions and treatment history of drug overdose decedents aged 10–19 years (N = 1,871), overall and by age group — State Unintentional Drug Overdose Reporting System, 43 jurisdictions,* July 2019–December 2021†,§

Abbreviations: SUD = substance use disorders; SUDORS = State Unintentional Drug Overdose Reporting System.

*Alaska, Arizona, Arkansas, Colorado, Connecticut, Delaware, District of Columbia, Florida, Georgia, Hawaii, Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Kansas, Kentucky, Louisiana, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, Michigan, Minnesota, Mississippi, Missouri, Montana, Nebraska, Nevada, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New Mexico, North Carolina, Ohio, Oklahoma, Oregon, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, South Dakota, Tennessee, Utah, Vermont, Virginia, Washington, West Virginia, and Wisconsin. Arkansas, Florida, Hawaii, Illinois, Indiana, Louisiana, Missouri, and Washington reported deaths from counties that accounted for ≥75% of drug overdose deaths in the state in 2017, per SUDORS funding requirements; all other jurisdictions reported deaths from the full jurisdiction. Jurisdictions were included if data were available for at least one 6-month period (July–December 2019, January–June 2020, July–December 2020, January–June 2021, or July–December 2021) and coroner and medical examiner reports were available for ≥75% of deaths in the included period or periods. Analysis was restricted to decedents with an available coroner and medical examiner report.

†Any mental health history includes at least one of the following: depression diagnosis; anxiety diagnosis; other mental health diagnosis; suicide attempt, ideation, or self-harm; or mental health or SUD treatment.

§Diagnoses are not mutually exclusive.

Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. 2022;71(50):1576-1582. © 2022 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)